Stop The Madness!

Judicial Activist Functional Dysfunction: National Injunctions

To describe national injunctions as irrational and unimaginable, though appropriate, reveals a law-abiding person’s quintessential “loss for words.” Suffice it to say, that national injunctions are a reprehensible bastardization of American jurisprudence.

In a normal, and legal, court case, attorney(s) filing a lawsuit on behalf of someone or some group, represent only the plaintiffs, that is, those who are directly impacted by the order, therefore also impacted by the lawsuit. Common sense, right?

National injunctions are unique in that they are NOT ONLY filed on behalf of the plaintiffs, but on behalf of everyone—that is ALL Americans. (And apparently taxpayer dollars fund them to represent non-citizens as well, cf. Trump v. Hawaii).

All Americans are NOT represented by the plaintiffs’ attorney(s), though the audacious attorney(s) presume to speak for everyone. These left-wing attorneys take it upon themselves to represent ALL American citizens though the overwhelming majority of citizens DID NOT ask for representation. Nor did they seek counsel. Nor did they want a suit filed on their behalf. Not did they want a stay imposed against any Presidential order. Nor do they have a voice in the suit. These citizens are not heard nor represented. This goes against fundamental principles of attorney/client relationships. This turns Miranda rights on their head.

Bastardized, right? Of course, the left is operating nefariously because it is the only way to have their unpopular and rejected policies imposed on society. This also explains why the majority of these injunctions come out of the Ninth District Court in San Francisco, a telltale sign of the ethical bankruptcy of the liberal culture.

What Does This Functional Dysfunction Look Like In Real Life?

Trump v. Hawaii is a practical example. Keep in mind that you, as a non-party, are being represented by an attorney(s) you do not know, you did not hire, nor did you ask for their representation. Because of this, your safety is being compromised based on a lawsuit that you—as a U.S. taxpayer—are affected by, are de facto represented in, yet have no voice in.

Here is an abbreiviated timeline leading up to the SCOTUS case Trump v. Hawaii:

02/01/2017 – President Trump signed Executive Order No. 13769, Protecting the Nation From Foreign Terrorist Entry Into the United States. 82 Fed. Reg. 8977 (2017) (EO–1).

02/03/2017 – District Court for the Western District of Washington entered a temporary restraining order blocking the entry restrictions [this leftwing language “temporary restraining order” is actually a national injunction, or as Justice Clarence Thomas prefers “universal injunction”].

02/09/2017 – Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals denied the Government’s request to stay that order. Washington v. Trump, 847 F. 3d 1151 (2017) (per curiam)

03/06/2017 – EO-1 was revoked and President Trump signed Executive Order 13780 (EO-2), Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States. EO-2 included interim measures until completion of a worldwide review.

03/15/2017 – A district court judge of the District Court for the District of Hawaii (Hawaii, for God’s sake! A piddly island and a nobody judge controlling the entire mainline of the U.S.!) issued an injunction against the EO-2,.

03/15/2017 – A district court judge of the District Court of Maryland also entered a national injunction—International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP) v. Trump(!).

[Did you know that you were being represented by the IRAP lawyers???]

05/25/2017 – 4th Circuit upheld the 03/15/2017 national injunction; Trump v. IRAP

06/12/2017 – 9th Circuit upheld (shock!) Judge No-frigging-body from Hawaii’s national injunction; Trump v. Hawaii

06/26/2017 – U.S. Supreme Court stayed the lower court injunctions as applied to those who have no “credible claim of a bona fide relationship with a person or entity in the United States.” The Court also granted certiorari and set oral arguments for the fall term. **Justice Thomas, joined by Justices Alito, and Gorsuch, partially dissented, writing that the lower courts’ entire injunctions against the executive order should be stayed.

09/24/2017 – President Trump issued Proclamation No. 9645, Enhancing Vetting Capabilities and Processes for Detecting Attempted Entry Into the United States by Terrorists or Other Public-Safety Threats. 82 Fed. Reg. 45161.

06/26/2018 – SCOTUS handed down its 5-4 decision which nullified the District Court’s injunction.

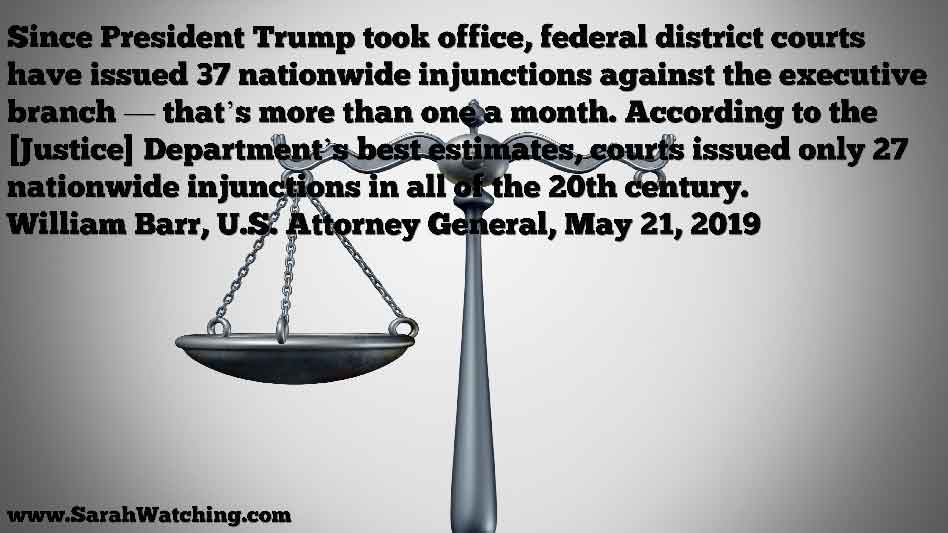

***Notice that it took from 02/01/2017 until 06/26/2018—almost 17 months(!)—to get the travel ban settled? Activist judges doing the bidding of special interests, putting Americans in danger by playing with national security, not to mention the hefty price tag this costs American taxpayers.

More Detail About The Abbreviated Timeline Above

Normally, SW does not recommend Wikipedia as authoritative reading (since leftists have taken control of its editing and are using it as a history revisionist tool; scary knowing how many students of all ages use this as a legit source). However, it is worthwhile to look at the Wikipedia entries for Trump v. Hawaii and Proclamation No. 9645, as well as their related links.

In articles such as these, the anti-American activists love to brag about their resistance to the Trump administration and their functional dysfunction in federal courts. Therefore, you’ll find extensive documentation regarding the multiple court cases, the dates, district courts, judges, people, and groups involved in these injunctions. It is quite disturbing. The billionaire donors spare no expense in their attempts to make America an open-borders, globalist controlled, communist shi*thole.

Left-wing Abuses Of Discretion AKA Utter Stupidity and Subversion

Multitudinous and ludicrous legal challenges rose against the travel ban (remember the faux outrage of the left calling it a “muslim ban” instead) and proclamation 9645. Reading these challenges provide the following insights:

- the lefty lawyers are completely moronic and ignorant of any SCOTUS precedent;

- they have zero respect for SCOTUS decisions, and

- they pile up challenges in one lawsuit, “forcing” the court to deliberate each absurd allegation (applying First Amendment rights to illegals, for instance), thus bogging down the court and the Justices.

All the while, this buys time for the reprobates to continue to destroy and weaken America.

SCOTUS 5-4 Decision In Trump v. Hawaii (Of Course)

Chief Justice Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Trump v. Hawaii. The last section says:

Because plaintiffs have not shown that they are likely to succeed on the merits of their claims, we reverse the grant of the preliminary injunction as an abuse of discretion. Winter v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 555 U. S. 7, 32 (2008). The case now returns to the lower courts for such further proceedings as may be appropriate. Our disposition of the case makes it unnecessary to consider the propriety of the nationwide scope of the injunction issued by the District Court.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals is reversed, and the case is remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion. It is so ordered.

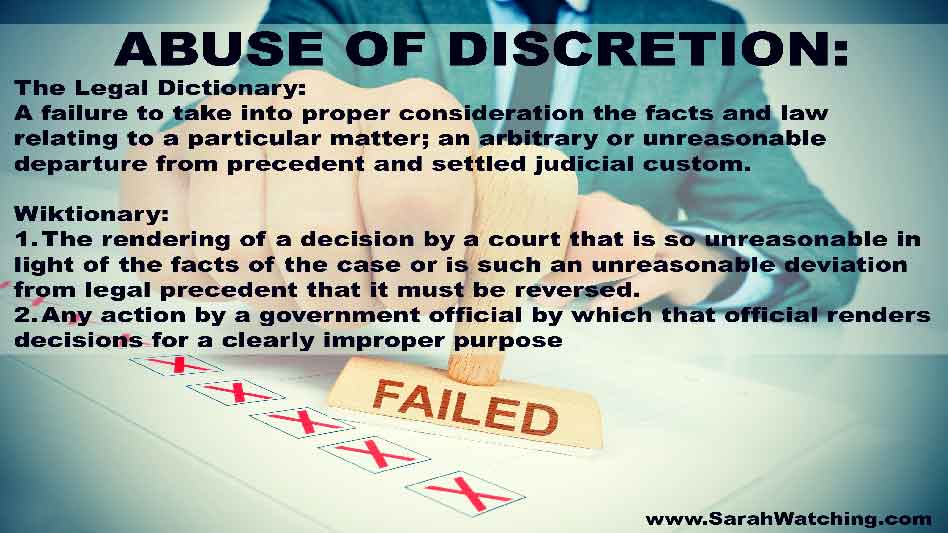

Abuse Of Discretion

It is easy to scan through this sentence: “…we reverse the grant of the preliminary injunction as an abuse of discretion.” as I did the first two or three times that I read through it. However, “abuse of discretion” is a legalese phrase carrying a heavy load of meaning. Here are two definitions along with an image for sharing just exactly what the Supreme Court said about the hacks who wrote up this lawsuit, as well as the hacks at the Ninth Circuit Court who upheld it.

The Legal Dictionary — A failure to take into proper consideration the facts and law relating to a particular matter; an arbitrary or unreasonable departure from precedent and settled judicial custom.

Wiktionary —

- (law) The rendering of a decision by a court that is so unreasonable in light of the facts of the case or is such an unreasonable deviation from legal precedent that it must be reversed.

- (law) Any action by a government official by which that official renders decisions for a clearly improper purpose

Check out some of the phrases:

- Unreasonable departure?

- So unreasonable in light of the facts?

- Such an unreasonable deviation from legal precedent?

- For a clearly improper purpose?

In other words, a big, fat, waste of time while people from banned muslim majority countries swarmed into out country. And btw, no one ever said that all muslims are terrorists. However, it is true that all terrorists are muslims. Reality, people!

Justice Clarence Thomas Rightly Points Out The Dubious Nature of National Injunctions

Though Chief Justice Roberts dusted off the issue of nationwide injunctions, not so with Justice Clarence Thomas. The one Justice that can be counted on to uphold the Constitution rightly questions a) the authority of district courts to impose universal injunctions and b) the validity of these injunctions in courts of equity.

SW highly recommends reading Justice Thomas’ concurrence in Trump v. Hawaii.

Justice Thomas Attacks National Injunctions Armed With A Vast Amount Of Founding Documents, Constitutional Law, And Supreme Court Precedent

Following are the major points of Justice Thomas’ opinion in Trump v. Hawaii with relative information inserted from cited cases and/or resources. When you realize just how much has been written on this issue, it becomes obvious that the judicial activists are extremely moronic or sinister, or both, therefore living up to their full-fledged legalese name—abusers of discretion.

Justice Thomas’ Concurrence in Trump v. Hawaii

In his concurrence with the majority opinion in Trump v. Hawaii, Justice Clarence Thomas addresses some of the many problems with the basic premise of the case. (Though I am not a lawyer, these seem Law 101 issues that even the C-minus law students from Hawaii and California should have known).

Thomas castigates national injunctions, or universal injunctions as he prefers to call them, as follows (underlines are mine):

Merits aside, I write separately to address the remedy that the plaintiffs sought and obtained in this case. The District Court imposed an injunction that barred the Government from enforcing the President’s Proclamation against anyone, not just the plaintiffs.

Denouncing the increasing number of “national,” aka “universal” injunctions, Thomas points out that district courts, including the one in Hawaii, “have begun imposing universal injunctions without considering their authority to grant such sweeping relief.” Universal injunctions impair the normal process of the federal judiciary causing the entire system to operate under duress—a lose-lose for the American people and the Judicial System.

Hammering home the questionable district court authority in matters of national significance, Thomas adds, “And they appear to be inconsistent with longstanding limits on equitable relief and the power of Article III courts. If their popularity continues, this Court must address their legality.”

Brief Outline of Thomas’ Concurrence With Snippets Of Cited Resources

I. If district courts have any authority to issue universal injunctions, that authority must come from a statute or the Constitution.

A. No statute expressly grants district courts the power to issue universal injunctions. So the only possible bases for these injunctions are

-

-

- a generic statute that authorizes equitable relief or

- the courts’ inherent constitutional authority.

-

Neither of those sources would permit a form of injunctive relief that is “[in]consistent with our history and traditions.”

II. National, aka universal, injunctions are in conflict with several traditional rules of equity, as well as the original understanding of the judicial role, including (lettering mine)

A. equity courts do not provide relief beyond the parties to the case,

B. judicial power is fundamentally the power to render judgments in individual cases,

C. the judiciary’s role about who can sue to vindicate certain rights is limited,

D, jurists in the latter half of the 20th century erroneously began to conceive of the judicial role in terms of resolving general questions of legality, instead of addressing those questions only insofar as they are necessary to resolve individual cases and controversies.

Thomas buttresses these statements using Constitutional Law and prior Supreme Court cases. He cites Missouri v. Jenkins, Blackstone, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and anti-Federalists The Federal Farmer and Brutus, who all concur on the subject of limitations on district court authority.

Missouri v. Jenkins (1995), 18-year old school segregation litigation in support of standing limitation on district court authority, snippets from Justice Thomas’ concurring opinion:

Judges have directed or managed the reconstruction of entire institutions and bureaucracies, with little regard for the inherent limitations on their authority.

Throughout his discussion, Blackstone emphasized that courts of equity must be governed by rules and precedents no less than the courts of law. “[I]f a court of equity were still at sea, and floated upon the occasional opinion which the judge who happened to preside might entertain of conscience in every particular case, the inconvenience that would arise from this uncertainty, would be a worse evil than any hardship that could follow from rules too strict and inflexible.” Id., at 440. If their remedial discretion had not been cabined, Blackstone warned, equity courts would have undermined the rule of law and produced arbitrary government. “[The judiciary’s] powers would have become too arbitrary to have been endured in a country like this, which boasts of being governed in all respects [ MISSOURI v. JENKINS, ___ U.S. ___ (1995) , 16] by law and not by will.” Ibid. (footnote omitted); see also 1 id., at 61-62.

The Federal Farmer hoped that the Constitution’s mention of equity jurisdiction was not “intended to lodge an arbitrary power or discretion in the judges, to decide as their conscience, their opinions, their caprice, or their politics might dictate.” Id., at 322-323.

So cautioned, the Framers approached equity with suspicion. As Thomas Jefferson put it, “Relieve the judges from the rigour of text law, and permit them, with pretorian discretion, to wander into it’s equity, and the whole legal system becomes uncertain.” 9 Papers of Thomas Jefferson 71 (J. Boyd ed. 1954). Suspicion of judicial discretion led to criticism of Article III during the ratification of the Constitution. Anti-Federalists attacked the Constitution’s extension of the federal judicial power to “Cases, in Law and Equity,” arising under the Constitution and federal statutes. According to the Anti-Federalists, the reference to equity granted federal judges excessive discretion to deviate from the requirements of the law. Said the “Federal Farmer,” “by thus joining the word equity with the word law, if we mean any thing, we seem to mean to give the judge a discretionary power.” Federal Farmer No. 15, January 18, 1788, in The Complete Anti-Federalist 322 (H. Storing ed. 1981) (hereinafter Storing). He hoped that the Constitution’s mention of equity jurisdiction was not “intended to lodge an arbitrary power or discretion in the judges, to decide as their conscience, their opinions, their caprice, or their politics might dictate.” Id., at 322-323. 4 Another Anti-Federalist, Brutus, argued that [ MISSOURI v. JENKINS, ___ U.S. ___ (1995) , 17] the equity power would allow federal courts to “explain the constitution according to the reasoning spirit of it, without being confined to the words or letter.” Brutus No. 11, January 31, 1788, id., at 419. This, predicted Brutus, would result in the growth of federal power and the “entire subversion of the legislative, executive and judicial powers of the individual states.” Id., at 420. See G. McDowell, Equity and the Constitution 43-44 (1982).

Hamilton described Article III “equity” as a jurisdiction over certain types of cases rather than as a broad remedial power

At the very least, given the Federalists’ public explanation during the ratification of the federal equity power, we should exercise the power to impose equitable remedies only sparingly, subject to clear rules guiding its use.

The separation of powers imposes additional restraints on the judiciary’s exercise of its remedial powers. To be sure, this is not a case of one branch of Government encroaching on the prerogatives of another, but rather of the power of the Federal Government over the States. Nonetheless, what the federal courts cannot do at the federal level they cannot do against the States; in either case, Article III courts are constrained by the inherent constitutional limitations on their powers. There simply are certain things that courts, in order to remain courts, cannot and should not do. There is no difference between courts running school systems or prisons and courts running executive branch agencies.

As Alexander Hamilton explained the limited authority of the federal courts: “The courts must declare the sense of the law; and if they should be disposed to exercise WILL instead of JUDGMENT, the consequence would equally be the substitution of their pleasure to that of the legislative body.” The Federalist No. 78, at 526. Federal judges cannot make the fundamentally political decisions as to which priorities are to receive funds and staff, which educational goals are to be sought, and which values are to be taught. When federal judges undertake such local, day-to-day tasks, they detract from the independence and dignity of the federal courts and intrude into areas in which they have [ MISSOURI v. JENKINS, ___ U.S. ___ (1995) , 22] little expertise. Cf. Mishkin, Federal Courts as State Reformers, 35 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 949 (1978).

Only by remaining aware of the limited nature of its remedial powers, and by giving the respect due to other governmental authorities, can the Judiciary ensure that its desire to do good will not tempt it into abandoning its limited role in our constitutional Government.

Even if segregation were present, we must remember that a deserving end does not justify all possible means. The desire to reform a school district, or any other institution, cannot so captivate the Judiciary that it forgets its constitutionally mandated role. Usurpation of the traditionally local control over education not only takes the judiciary beyond its proper sphere, it also deprives the States and their elected officials of their constitutional powers. At some point, we must recognize that the judiciary is not omniscient, and that all problems do not require a remedy of constitutional proportions.

Expanding on #1 from IA above, Thomas continues: “This Court has never treated general statutory grants of equitable authority as giving federal courts a freewheeling power to fashion new forms of equitable remedies.” This is reinforced by the 1945 Supreme Court case Guaranty Trust Co. v. York which cited Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins involving the question of geography.

Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins was not an endeavor to formulate scientific legal terminology. It expressed a policy that touches vitally the proper distribution of judicial power between State and federal courts.

Judge Augustus N. Hand thus summarized below the fatal objection to such inroads upon Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins: ‘In my opinion it would be a mischievous practice to disregard state statutes of limitation whenever federal courts think that the result of adopting them may be inequitable. Such procedure would promote the choice of United States rather than of state courts in order to gain the advantage of different laws. The main foundation for the criticism of Swift v. Tyson was that a litigant in cases where federal jurisdiction is based only on diverse citizenship may obtain a more favorable decision by suing in the United States courts.’ 2 Cir., 143 F.2d 503, 529, 531.

The source of substantive rights enforced by a federal court under diversity jurisdiction, it cannot be said too often, is the law of the States. Whenever that law is authoritatively declared by a State, whether its voice be the legislature or its highest court, such law ought to govern in litigation founded on that law, whether the forum of application is a State or a federal court and whether the remedies be sought at law or may be had in equity.

Expanding on #2 under Outline IA, Thomas’ continues: “The same is true of the courts’ inherent constitutional authority to grant equitable relief, assuming any such authority exists. See Jenkins, 515 U. S., at 124 (THOMAS, J., concurring). This authority is also limited by the traditional rules of equity that existed at the founding.” In addition to Missouri v. Jenkins, support for this statement is also garnered from Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist No. 78.

Hamilton explained that the judiciary would be “bound down by strict rules and precedents which serve to define and point out their duty in every particular case that comes before them.” The Federalist No. 78, p. 471 and page 466…

Whoever attentively considers the different departments of power must perceive, that, in a government in which they are separated from each other, the judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution; because it will be least in a capacity to annoy or injure them. The Executive not only dispenses the honors, but holds the sword of the community. The legislature not only commands the purse, but prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments.

For I agree, that “there is no liberty, if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers.”

There is no position which depends on clearer principles, than that every act of a delegated authority, contrary to the tenor of the commission under which it is exercised, is void. No legislative act, therefore, contrary to the Constitution, can be valid. To deny this, would be to affirm, that the deputy is greater than his principal; that the servant is above his master; that the representatives of the people are superior to the people themselves; that men acting by virtue of powers, may do not only what their powers do not authorize, but what they forbid.

Considerate men, of every description, ought to prize whatever will tend to beget or fortify that temper in the courts: as no man can be sure that he may not be to-morrow the victim of a spirit of injustice, by which he may be a gainer to-day. And every man must now feel, that the inevitable tendency of such a spirit is to sap the foundations of public and private confidence, and to introduce in its stead universal distrust and distress.

Based on the Constitution, the Founders, and past Supreme Courts cases, district courts do not have the authority to invoke universal injunctions.

In Section II, the erudite Justice points out multiple conflicts between national injunctions and judiciary power and roles.

In a democracy, it is “we the people” who elect officials to run the government. However, district court judicial activists take it upon themselves to second guess the President, i.e. second guess the electorate, and bar “the Government from enforcing the President’s Proclamation against anyone, not just the plaintiffs.”

Though some have tried to claim semblance with a type of class-action suit, Thomas dismisses this by stating the original objections—more parties than the plaintiffs are involved.

(True, one of the recognized bases for an exercise of equitable power was the avoidance of “multiplicity of suits.” Bray 426; accord, 1 Pomeroy §243. Courts would employ “bills of peace” to consider and resolve a number of suits in a single proceeding. Id., §246. And some authori- Cite as: 585 U. S. ____ (2018) 7 THOMAS, J., concurring ties stated that these suits could be filed by one plaintiff on behalf of a number of others. Id., §251. But the “general rule” was that “all persons materially interested . . . in the subject-matter of a suit, are to be made parties to it . . . , however numerous they may be, so that there may be a complete decree, which shall bind them all.” Story §72, at 61 (emphasis added). And, in all events, these “protoclass action[s]” were limited to a small group of similarly situated plaintiffs having some right in common. Bray 426–427; see also Story §120, at 100 (explaining that such suits were “always” based on “a common interest or a common right”).

In Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Assn (2018), Thomas wrote::

Those precedents appear to be in tension with traditional limits on judicial authority. Early American courts did not have a severability doctrine. See Walsh, Partial Unconstitutionality, 85 N. Y. U. L. Rev. 738, 769 (2010) (Walsh). They recognized that the judicial power is, fundamentally, the power to render judgments in individual cases. See id., at 755; Baude, The Judgment Power, 96 Geo. L. J. 1807, 1815 (2008). Judicial review was a byproduct of that process. See generally P. Hamburger, Law and Judicial Duty (2008); Prakash & Yoo, The Origins of Judicial Review, 70 U. Chi. L. Rev. 887 (2003).

Misuses of judicial power, Hamilton reassured the people of New York, could not threaten “the general liberty of the people” because courts, at most, adjudicate the rights of “individual[s].” Federalist No. 78, at 466. (from Trump v. Hawaii, Thomas concurring).

Thomas cites the recent 2016 Supreme Court case Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins to ascertain the judiciary’s limited role in decisions about who could sue to vindicate certain rights.

To understand the limits that standing imposes on “the judicial Power,” therefore, we must “refer directly to the traditional, fundamental limitations upon the powers of commonlaw courts.” Honig v. Doe, 484 U. S. 305, 340 (1988) (Scalia, J., dissenting). These limitations preserve separation of powers by preventing the judiciary’s entanglement in disputes that are primarily political in nature. This concern is generally absent when a private plaintiff seeks to enforce only his personal rights against another private party.

Common-law courts, however, have required a further showing of injury for violations of “public rights”–rights that involve duties owed “to the whole community, considered as a community, in its social aggregate capacity.” 4 Blackstone *5. Such rights include “free navigation of waterways, passage on public highways, and general compliance with regulatory law.” Woolhander & Nelson, 102 Mich. L. Rev., at 693.

The separation-of-powers concerns underlying our public-rights decisions are not implicated when private individuals sue to redress violations of their own private rights. But, when they are implicated, standing doctrine keeps courts out of political disputes by denying private litigants the right to test the abstract legality of government action. See Schlesinger, supra, at 222. And by limiting Congress’ ability to delegate law enforcement authority to private plaintiffs and the courts, standing doctrine preserves executive discretion. See Lujan, supra, [Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, Scalia writing for the majority] at 577 (” ‘To permit Congress to convert the undifferentiated public interest in executive officers’ compliance with the law into an ‘individual right’ vindicable in the courts is to permit Congress to transfer from the President to the courts the Chief Executive’s most important constitutional duty, to ‘take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed’ “).

Section II makes the case for the recent onslaught of universal injunctions’ disregard of the basic notion of who is represented in a case. This puts on full display the complete contempt for those who are affected by the case but have no voice in it (you and me):

This Court has long respected these traditional limits on equity and judicial power. See, e.g., Scott v. Donald, 165 U. S. 107, 115 (1897) (rejecting an injunction based on the theory that the plaintiff “so represents [a] class” whose rights were infringed by a statute as “too conjectural to furnish a safe basis upon which a court of equity ought to grant an injunction”). (From Hawaii v. Trump)

Justice Shiras wrote in Scott V. Donald:

The theory of the decree is that the plaintiff is one of a class of persons whose rights are infringed and threatened, and that he so represents such class that he may pray an injunction on behalf of all persons that constitute it. It is, indeed, possible that there may be others in like case with the plaintiff, and that such persons may be numerous; but such a state of facts is too conjectural to furnish a safe basis upon which a court of equity ought to grant an injunction.

The decree is also objectionable because it enjoins persons not parties to the suit. This is not a case where the defendants named represent those not named. Nor is there alleged any conspiracy between the parties defendant and other unknown parties. The acts complained of are tortious, and do not grow out of any common action or agreement between constables and sheriffs of the state of South Carolina. We have, indeed, a right to presume that such officers, though not named in this suit, will, when advised that certain provisions of the act in question have been pronounced unconstitutional by the court to which the constitution of the United States refers such questions, voluntarily refrain from enforcing such provisions; but we do not think it comports with well-settled principles of equity procedure to include them in an injunction in a suit in which they were not heard or represented, or to subject them to penalties for contempt in disregarding such an injunction. Fellows v. Fellows, 4 Johns. Ch. 25, citing Iveson v. Harris, 7 Ves. 257.

Thomas’ last paragraph of Section II says:

No persuasive defense has yet been offered for the practice. Defenders of these injunctions contend that they ensure that individuals who did not challenge a law are treated the same as plaintiffs who did, and that universal injunctions give the judiciary a powerful tool to check the Executive Branch. See Amdur & Hausman, Nationwide Injunctions and Nationwide Harm, 131 Harv. L. Rev. Forum 49, 51, 54 (2017); Malveaux, Class Actions, Civil Rights, and the National Injunction, 131 Harv. L. Rev. Forum 56, 57, 60–62 (2017). But these arguments do not explain how these injunctions are consistent with the historical limits on equity and judicial power. They at best “boi[l] down to a policy judgment” about how powers ought to be allocated among our three branches of government. Perez v. Mortgage Bankers Assn., 575 U. S. ___, ___ (2015) (THOMAS, J., concurring in judgment) (slip op., at 23). But the people already made that choice when they ratified the Constitution.

In Perez v. Mortgage Bankers, Thomas wrote:

That line of precedents, beginning with Bowles v. Seminole Rock & Sand Co., 325 U. S. 410 (1945), requires judges to defer to agency interpretations of regulations, thus, as happened in these cases, giving legal effect to the interpretations rather than the regulations themselves. Because this doctrine effects a transfer of the judicial power to an executive agency, it raises constitutional concerns. This line of precedents undermines our obligation to provide a judicial check on the other branches, and it subjects regulated parties to precisely the abuses that the Framers sought to prevent.

To preserve that accountability, we have held that executive officers must be subject to removal by the President to ensure accountability within the Executive Branch. See Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Bd., 561 U. S. 477, 495 (2010); see also Morrison, supra, at 709 (opinion of SCALIA, J.)

“It is not for us to determine, and we have never presumed to determine, how much of the purely executive powers of government must be within the full control of the President. The Constitution prescribes that they all are” Justice Scalia, Morrison v. Olson (1988), dissenting.

Summary

When all is said and done, the Supreme Court has the obligation to uphold the Constitution. Supreme Court Justices, and certainly Judges in any court, should judge based on the law—not political ideology.

As Justice Thomas said in Perez v. Mortgage Bankers Assn. (2014), “The Legislature and Executive may be swayed by popular sentiment to abandon the strictures of the Constitution or other rules of law. But the Judiciary, insulated from both internal and external sources of bias, is duty bound to exercise independent judgment in applying the law.”

And Justice Scalia in Zuni Public School Dist. No. 89 v. Department of Education, (2007), “To be governed by legislated text rather than legislators’ intentions is what it means to be ‘a Government of laws, not of men’” quoting in part Chief Justice John Marshall in the landmark case Marbury v. Madison (1803):

The government of the United States has been emphatically termed a government of laws, and not of men.

Yet the progressives, globalists, Democrats, all the leftists, in their wild, distorted, reprobate minds, have decided that they are above rules, laws, statutes, the Constitution, anything that is based on ratified principles governing a democracy.

Federal judges who do not uphold the Constitution can and should be impeached for not upholding the oath of office. In fact, leftist judges subversive to the Constitution must be impeached. Leftists in general must be pummeled at the ballot box and never allowed to hold any office again.

Solution To The Functional Dysfunction

The Supreme Court must put a stop to the judicial tyranny known as national/universal injunctions. In addition, reprimand is needed against leftist judges who sit on their judicial thrones issuing orders that affect the entire country. Again, they can easily be impeached.

As Justice Thomas sums up his opinion:

In sum, universal injunctions are legally and historically dubious. If federal courts continue to issue them, this Court is dutybound to adjudicate their authority to do so.

Agreed! SCOTUS is dutybound to stop the left’s functional dysfunction before they use it in even more destructive ways. The evil mind knows no bounds.

Comments are Closed